The Pitfalls of Emotional Investing

People often make decisions based on emotion instead of rational deliberation. For example, that one friend you have who bought a new car they couldn’t afford because it but felt so incredibly nice to sit in it. I have a confession: that wasn’t a friend, it was me. The car was a black Ford Mustang. After finalizing the purchase and paying cash for the car, I remember reviewing my bank account and realizing I only had $11 to my name. Oh, and the car too. I was seventeen years old at the time and it was certainly not a sound investment decision on my part, it was an impulsive and emotional decision. I did have a lot of fun with that car if you’re wondering. But the truth is, if I put that hard-earned cash to better use by investing it and enjoying compound growth over several years, I would have been much better off. With the benefit of hindsight and years of experience and financial education, I now realize that the opportunity cost of that car was much more than the initial purchase price.

When it comes to investing, human behavior may cause us to make decisions based on emotion and not on fundamentals or rational deliberation. It’s a natural tendency. If you’ve been investing for some time you will certainly remember the tech bubble of 2000. Leading into that market, you could have invested in almost any tech start up and seen overnight success. But as we all know, that soon came to a screeching halt. The market is largely driven by supply and demand paired with fear and greed, as illustrated in the diagram below. Leading up to the tech bubble, investors saw double–digit returns and got greedy. This was followed by fear, or in this case, shear panic in 2002 following the Nasdaq drop of nearly 77% from top to bottom.

Consider some of the market corrections we saw in 2018 that were partly fueled by social media tweets about looming trade war concerns. Did large companies all announce poor earnings? No. Did the Fed make significant announcements or changes to rates at the time? No. Did job numbers or GDP reports come in much lower than expected? No. If nothing fundamentally changed, what caused the rise and fall of stock prices in those volatile times? Emotion.

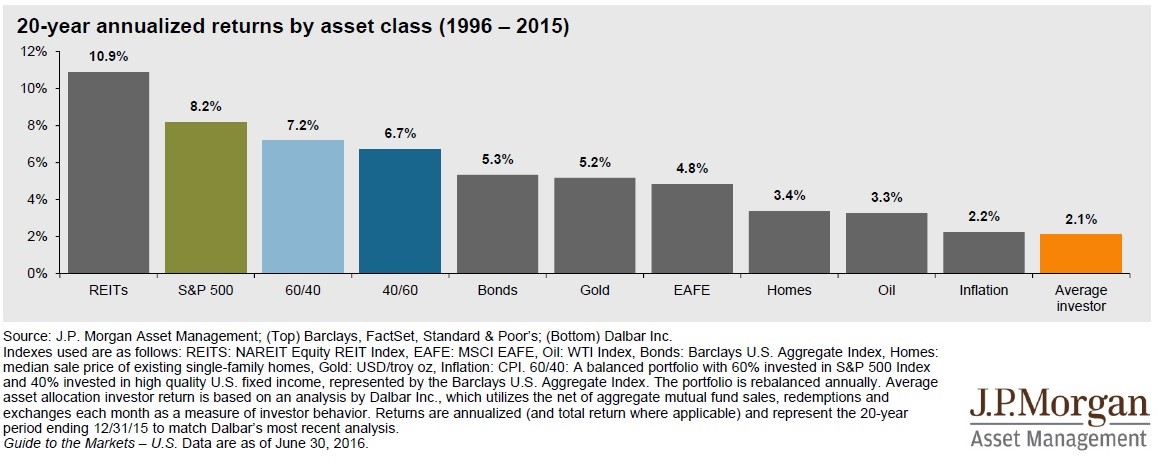

Studies by Dalbar’s Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (see the chart by J.P. Morgan, below) have shown that, over the last twenty years, the average investor has experienced a return of just 2.1% while the S&P 500 returned 8.2%.

What accounts for this difference of more than 6% return on investment? A lot of it can be blamed on emotional decision-making, lack of discipline, and failure to diversify. Consider the lag effect and confidence when markets are high and peaking. This is generally a time that many investors are buying into the market, when in fact this is the ultimate time to sell and become more defensive or conservative. On the other hand, when markets are at the bottom it is a great opportunity to purchase stock or to take more aggressive positions. Think back to the 2008 financial crisis, when the S&P 500 lost 38% in a single year and every analyst featured on CNBC feared that the world was coming to an end. During that time, CNBC interviewed Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffet. I vividly remember the interview. Buffet, always the contrarian, compared the opportunity in the market to toilet paper being on sale at Walmart: he wouldn’t run away, he would be a buyer. A simple analogy from one of the smartest investors of our time.

During the crisis, many investors were pulling money out of the markets and moving it to cash to “wait on the sidelines.” After watching the Dow Jones Industrial Average drop from its peak of over 14,000 points in October 2007 to under 7,000 points by March 2009, and then climb back above 10,000 in less than nine months, I remember asking people when they were going to get back in. Most of them had no response, no plan. Many people never took the time to assess their re-entry point and timidly sat on the sidelines in cash, some never reinvesting back into their portfolios. Today’s market is almost double that of the pre-crisis peak. If these investors had stuck to their game plan, patiently waiting out only a few years of recovery following the worst crash since the Great Depression, they would have realized significant gains today and would have been even better off than they were before the crash.

Emotion can lead some investors to concentrate their portfolio in too few individual positions as well. I’ll never forget talking to a client, during the decline of General Motors, about the importance of diversification in his portfolio. This gentleman was a high school dropout who retired as a janitor, sweeping up the manufacturing facilities at one of the GM plants. He understood the importance of saving money and had fully invested his 401(k) in GM stock during a rising time for the company and auto industry. At the time of his retirement, he found himself not only fully invested in GM stock in his 401(k), but also his IRA, his wife’s retirement accounts, and their taxable nonretirement assets. This gentleman’s net worth was nearly $3,000,000 at the time of his retirement, not bad for a high school dropout. Despite conversations about his concentration risk and the importance of diversification and exit strategies, he stubbornly stayed invested in GM stock until all his combined accounts were worth less than $200,000 and GM neared bankruptcy. He was in denial for a long time, but he eventually realized that he let his emotions take control. The company he loved, and for which he worked so hard for nearly 50 years, was not the company he should have bet his entire retirement on. He was emotionally attached to GM because of his history with the company and the fond memories he had from his years of working there. He also was overconfident, as he had seen nothing but increases in GM’s production and the consistent growth of the auto industry, and he was comforted by the leadership he worked under during his tenure. This emotional attachment and overconfidence lead to one individual stock comprising his entire portfolio.

Technology has only exacerbated the problem with emotional investing and decision-making. Today, self-directed investors can get market information almost as quickly as a professional wealth manager, and quotes in real time. With this immediate flow of information, many investors make knee-jerk reactions to news because they fear monetary loss or missed opportunities. Part of what separates these self-directed investors from professional wealth managers is the ability to manage the emotional side of the markets through established processes and deliberative analysis. As professional wealth managers, our job is to take all the available data, sort through it, make sense of it, and act in accordance with pre-established goals and objectives, leaving emotion out of the equation.

As an advisor, it’s easy to discuss long-term trends with clients in the face of a poor year or a poor quarter. It is another thing to have that discussion during the boom years. If the markets have shown us anything over the years, it is that they themselves have no concept of emotion, fear, or greed. They just keep chugging along. Therefore, investors shouldn’t make decisions based on emotion, fear, or greed. This is easier said than done. It is difficult for some investors to grasp the concept of a strategy coming to fruition over several years, as opposed to the instant gratification of immediate investment success. I often find myself reminding my clients that their net worth was built over a lifetime and their investments should work equally as long and hard for them. The idea of the “get rich quick” scheme is simply not a realistic investment strategy. As advisors, we must act as educators and coaches of our clients, keeping them on track and helping them overcome the urge to make poor emotional investment decisions.

It’s no secret why most investors enjoy their best returns in their 401(k) plans. It’s not because they offer a better investment array or product offering. To the contrary, most 401(k) plans limit the investment options to a select group of mutual funds and limit the number of transactions allowed in a given time period. So why are their returns often so much better? It is because, within a 401(k) plan, employees are forced to diversify, stay disciplined, and dollar cost average into a defined investment plan that works over the life of their career.

The moral of the story? Stay disciplined while investing. Despite market movement and volatility, think logically and strategically about your investments. Good, sound financial planning is often the foundation to helping determine the right amount of risk and type of investment strategy you need to be confident, comfortable, and to stay the course.

Any time you have questions regarding your account, please reach out to your Spotlight Asset Group Wealth Manager. If you are not an existing client but are interested in discussing your financial situation with a professional advisor, contact us today.

Brad Tatar

Join the Spotlight Asset Group Newsletter

The Pitfalls of Emotional Investing

People often make decisions based on emotion instead of rational deliberation. For example, that one friend you have who bought a new car they couldn’t afford because it but felt so incredibly nice to sit in it. I have a confession: that wasn’t a friend, it was me. The car was a black Ford Mustang. After finalizing the purchase and paying cash for the car, I remember reviewing my bank account and realizing I only had $11 to my name. Oh, and the car too. I was seventeen years old at the time and it was certainly not a sound investment decision on my part, it was an impulsive and emotional decision. I did have a lot of fun with that car if you’re wondering. But the truth is, if I put that hard-earned cash to better use by investing it and enjoying compound growth over several years, I would have been much better off. With the benefit of hindsight and years of experience and financial education, I now realize that the opportunity cost of that car was much more than the initial purchase price.

When it comes to investing, human behavior may cause us to make decisions based on emotion and not on fundamentals or rational deliberation. It’s a natural tendency. If you’ve been investing for some time you will certainly remember the tech bubble of 2000. Leading into that market, you could have invested in almost any tech start up and seen overnight success. But as we all know, that soon came to a screeching halt. The market is largely driven by supply and demand paired with fear and greed, as illustrated in the diagram below. Leading up to the tech bubble, investors saw double–digit returns and got greedy. This was followed by fear, or in this case, shear panic in 2002 following the Nasdaq drop of nearly 77% from top to bottom.

Consider some of the market corrections we saw in 2018 that were partly fueled by social media tweets about looming trade war concerns. Did large companies all announce poor earnings? No. Did the Fed make significant announcements or changes to rates at the time? No. Did job numbers or GDP reports come in much lower than expected? No. If nothing fundamentally changed, what caused the rise and fall of stock prices in those volatile times? Emotion.

Studies by Dalbar’s Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (see the chart by J.P. Morgan, below) have shown that, over the last twenty years, the average investor has experienced a return of just 2.1% while the S&P 500 returned 8.2%.

What accounts for this difference of more than 6% return on investment? A lot of it can be blamed on emotional decision-making, lack of discipline, and failure to diversify. Consider the lag effect and confidence when markets are high and peaking. This is generally a time that many investors are buying into the market, when in fact this is the ultimate time to sell and become more defensive or conservative. On the other hand, when markets are at the bottom it is a great opportunity to purchase stock or to take more aggressive positions. Think back to the 2008 financial crisis, when the S&P 500 lost 38% in a single year and every analyst featured on CNBC feared that the world was coming to an end. During that time, CNBC interviewed Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffet. I vividly remember the interview. Buffet, always the contrarian, compared the opportunity in the market to toilet paper being on sale at Walmart: he wouldn’t run away, he would be a buyer. A simple analogy from one of the smartest investors of our time.

During the crisis, many investors were pulling money out of the markets and moving it to cash to “wait on the sidelines.” After watching the Dow Jones Industrial Average drop from its peak of over 14,000 points in October 2007 to under 7,000 points by March 2009, and then climb back above 10,000 in less than nine months, I remember asking people when they were going to get back in. Most of them had no response, no plan. Many people never took the time to assess their re-entry point and timidly sat on the sidelines in cash, some never reinvesting back into their portfolios. Today’s market is almost double that of the pre-crisis peak. If these investors had stuck to their game plan, patiently waiting out only a few years of recovery following the worst crash since the Great Depression, they would have realized significant gains today and would have been even better off than they were before the crash.

Emotion can lead some investors to concentrate their portfolio in too few individual positions as well. I’ll never forget talking to a client, during the decline of General Motors, about the importance of diversification in his portfolio. This gentleman was a high school dropout who retired as a janitor, sweeping up the manufacturing facilities at one of the GM plants. He understood the importance of saving money and had fully invested his 401(k) in GM stock during a rising time for the company and auto industry. At the time of his retirement, he found himself not only fully invested in GM stock in his 401(k), but also his IRA, his wife’s retirement accounts, and their taxable nonretirement assets. This gentleman’s net worth was nearly $3,000,000 at the time of his retirement, not bad for a high school dropout. Despite conversations about his concentration risk and the importance of diversification and exit strategies, he stubbornly stayed invested in GM stock until all his combined accounts were worth less than $200,000 and GM neared bankruptcy. He was in denial for a long time, but he eventually realized that he let his emotions take control. The company he loved, and for which he worked so hard for nearly 50 years, was not the company he should have bet his entire retirement on. He was emotionally attached to GM because of his history with the company and the fond memories he had from his years of working there. He also was overconfident, as he had seen nothing but increases in GM’s production and the consistent growth of the auto industry, and he was comforted by the leadership he worked under during his tenure. This emotional attachment and overconfidence lead to one individual stock comprising his entire portfolio.

Technology has only exacerbated the problem with emotional investing and decision-making. Today, self-directed investors can get market information almost as quickly as a professional wealth manager, and quotes in real time. With this immediate flow of information, many investors make knee-jerk reactions to news because they fear monetary loss or missed opportunities. Part of what separates these self-directed investors from professional wealth managers is the ability to manage the emotional side of the markets through established processes and deliberative analysis. As professional wealth managers, our job is to take all the available data, sort through it, make sense of it, and act in accordance with pre-established goals and objectives, leaving emotion out of the equation.

As an advisor, it’s easy to discuss long-term trends with clients in the face of a poor year or a poor quarter. It is another thing to have that discussion during the boom years. If the markets have shown us anything over the years, it is that they themselves have no concept of emotion, fear, or greed. They just keep chugging along. Therefore, investors shouldn’t make decisions based on emotion, fear, or greed. This is easier said than done. It is difficult for some investors to grasp the concept of a strategy coming to fruition over several years, as opposed to the instant gratification of immediate investment success. I often find myself reminding my clients that their net worth was built over a lifetime and their investments should work equally as long and hard for them. The idea of the “get rich quick” scheme is simply not a realistic investment strategy. As advisors, we must act as educators and coaches of our clients, keeping them on track and helping them overcome the urge to make poor emotional investment decisions.

It’s no secret why most investors enjoy their best returns in their 401(k) plans. It’s not because they offer a better investment array or product offering. To the contrary, most 401(k) plans limit the investment options to a select group of mutual funds and limit the number of transactions allowed in a given time period. So why are their returns often so much better? It is because, within a 401(k) plan, employees are forced to diversify, stay disciplined, and dollar cost average into a defined investment plan that works over the life of their career.

The moral of the story? Stay disciplined while investing. Despite market movement and volatility, think logically and strategically about your investments. Good, sound financial planning is often the foundation to helping determine the right amount of risk and type of investment strategy you need to be confident, comfortable, and to stay the course.

Any time you have questions regarding your account, please reach out to your Spotlight Asset Group Wealth Manager. If you are not an existing client but are interested in discussing your financial situation with a professional advisor, contact us today.

Brad Tatar