Newsletter October 2019

Newsletter October 2019

Join the Spotlight Asset Group Newsletter

Newsletter October 2019

Newsletter July 2019

Newsletter July 2019

Read the latest Spotlight Asset Group company news, market updates and employee Spotlight in the July 2019 Quarterly Newsletter.

Join the Spotlight Asset Group Newsletter

Newsletter July 2019

Read the latest Spotlight Asset Group company news, market updates and employee Spotlight in the July 2019 Quarterly Newsletter.

The Pitfalls of Emotional Investing

The Pitfalls of Emotional Investing

People often make decisions based on emotion instead of rational deliberation. For example, that one friend you have who bought a new car they couldn’t afford because it but felt so incredibly nice to sit in it. I have a confession: that wasn’t a friend, it was me. The car was a black Ford Mustang. After finalizing the purchase and paying cash for the car, I remember reviewing my bank account and realizing I only had $11 to my name. Oh, and the car too. I was seventeen years old at the time and it was certainly not a sound investment decision on my part, it was an impulsive and emotional decision. I did have a lot of fun with that car if you’re wondering. But the truth is, if I put that hard-earned cash to better use by investing it and enjoying compound growth over several years, I would have been much better off. With the benefit of hindsight and years of experience and financial education, I now realize that the opportunity cost of that car was much more than the initial purchase price.

When it comes to investing, human behavior may cause us to make decisions based on emotion and not on fundamentals or rational deliberation. It’s a natural tendency. If you’ve been investing for some time you will certainly remember the tech bubble of 2000. Leading into that market, you could have invested in almost any tech start up and seen overnight success. But as we all know, that soon came to a screeching halt. The market is largely driven by supply and demand paired with fear and greed, as illustrated in the diagram below. Leading up to the tech bubble, investors saw double–digit returns and got greedy. This was followed by fear, or in this case, shear panic in 2002 following the Nasdaq drop of nearly 77% from top to bottom.

Consider some of the market corrections we saw in 2018 that were partly fueled by social media tweets about looming trade war concerns. Did large companies all announce poor earnings? No. Did the Fed make significant announcements or changes to rates at the time? No. Did job numbers or GDP reports come in much lower than expected? No. If nothing fundamentally changed, what caused the rise and fall of stock prices in those volatile times? Emotion.

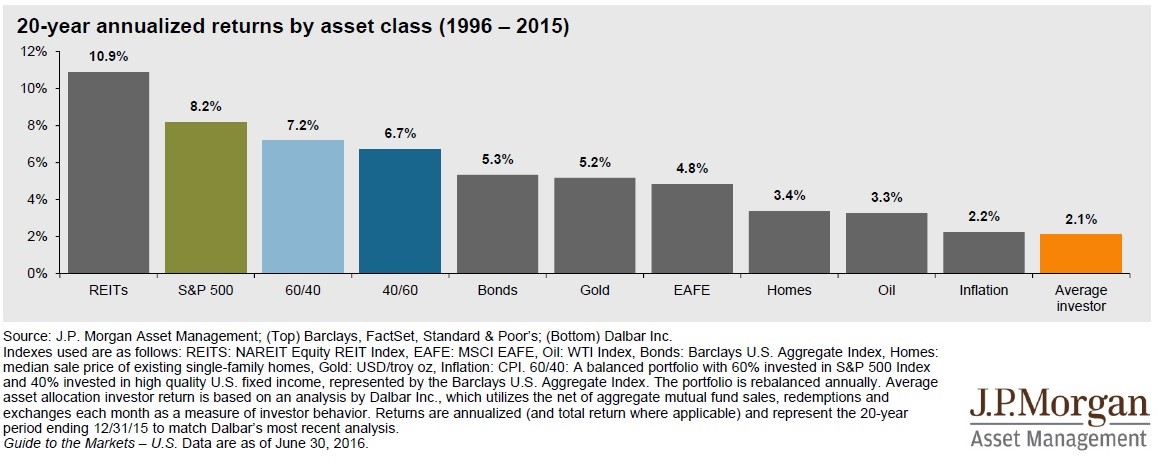

Studies by Dalbar’s Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (see the chart by J.P. Morgan, below) have shown that, over the last twenty years, the average investor has experienced a return of just 2.1% while the S&P 500 returned 8.2%.

What accounts for this difference of more than 6% return on investment? A lot of it can be blamed on emotional decision-making, lack of discipline, and failure to diversify. Consider the lag effect and confidence when markets are high and peaking. This is generally a time that many investors are buying into the market, when in fact this is the ultimate time to sell and become more defensive or conservative. On the other hand, when markets are at the bottom it is a great opportunity to purchase stock or to take more aggressive positions. Think back to the 2008 financial crisis, when the S&P 500 lost 38% in a single year and every analyst featured on CNBC feared that the world was coming to an end. During that time, CNBC interviewed Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffet. I vividly remember the interview. Buffet, always the contrarian, compared the opportunity in the market to toilet paper being on sale at Walmart: he wouldn’t run away, he would be a buyer. A simple analogy from one of the smartest investors of our time.

During the crisis, many investors were pulling money out of the markets and moving it to cash to “wait on the sidelines.” After watching the Dow Jones Industrial Average drop from its peak of over 14,000 points in October 2007 to under 7,000 points by March 2009, and then climb back above 10,000 in less than nine months, I remember asking people when they were going to get back in. Most of them had no response, no plan. Many people never took the time to assess their re-entry point and timidly sat on the sidelines in cash, some never reinvesting back into their portfolios. Today’s market is almost double that of the pre-crisis peak. If these investors had stuck to their game plan, patiently waiting out only a few years of recovery following the worst crash since the Great Depression, they would have realized significant gains today and would have been even better off than they were before the crash.

Emotion can lead some investors to concentrate their portfolio in too few individual positions as well. I’ll never forget talking to a client, during the decline of General Motors, about the importance of diversification in his portfolio. This gentleman was a high school dropout who retired as a janitor, sweeping up the manufacturing facilities at one of the GM plants. He understood the importance of saving money and had fully invested his 401(k) in GM stock during a rising time for the company and auto industry. At the time of his retirement, he found himself not only fully invested in GM stock in his 401(k), but also his IRA, his wife’s retirement accounts, and their taxable nonretirement assets. This gentleman’s net worth was nearly $3,000,000 at the time of his retirement, not bad for a high school dropout. Despite conversations about his concentration risk and the importance of diversification and exit strategies, he stubbornly stayed invested in GM stock until all his combined accounts were worth less than $200,000 and GM neared bankruptcy. He was in denial for a long time, but he eventually realized that he let his emotions take control. The company he loved, and for which he worked so hard for nearly 50 years, was not the company he should have bet his entire retirement on. He was emotionally attached to GM because of his history with the company and the fond memories he had from his years of working there. He also was overconfident, as he had seen nothing but increases in GM’s production and the consistent growth of the auto industry, and he was comforted by the leadership he worked under during his tenure. This emotional attachment and overconfidence lead to one individual stock comprising his entire portfolio.

Technology has only exacerbated the problem with emotional investing and decision-making. Today, self-directed investors can get market information almost as quickly as a professional wealth manager, and quotes in real time. With this immediate flow of information, many investors make knee-jerk reactions to news because they fear monetary loss or missed opportunities. Part of what separates these self-directed investors from professional wealth managers is the ability to manage the emotional side of the markets through established processes and deliberative analysis. As professional wealth managers, our job is to take all the available data, sort through it, make sense of it, and act in accordance with pre-established goals and objectives, leaving emotion out of the equation.

As an advisor, it’s easy to discuss long-term trends with clients in the face of a poor year or a poor quarter. It is another thing to have that discussion during the boom years. If the markets have shown us anything over the years, it is that they themselves have no concept of emotion, fear, or greed. They just keep chugging along. Therefore, investors shouldn’t make decisions based on emotion, fear, or greed. This is easier said than done. It is difficult for some investors to grasp the concept of a strategy coming to fruition over several years, as opposed to the instant gratification of immediate investment success. I often find myself reminding my clients that their net worth was built over a lifetime and their investments should work equally as long and hard for them. The idea of the “get rich quick” scheme is simply not a realistic investment strategy. As advisors, we must act as educators and coaches of our clients, keeping them on track and helping them overcome the urge to make poor emotional investment decisions.

It’s no secret why most investors enjoy their best returns in their 401(k) plans. It’s not because they offer a better investment array or product offering. To the contrary, most 401(k) plans limit the investment options to a select group of mutual funds and limit the number of transactions allowed in a given time period. So why are their returns often so much better? It is because, within a 401(k) plan, employees are forced to diversify, stay disciplined, and dollar cost average into a defined investment plan that works over the life of their career.

The moral of the story? Stay disciplined while investing. Despite market movement and volatility, think logically and strategically about your investments. Good, sound financial planning is often the foundation to helping determine the right amount of risk and type of investment strategy you need to be confident, comfortable, and to stay the course.

Any time you have questions regarding your account, please reach out to your Spotlight Asset Group Wealth Manager. If you are not an existing client but are interested in discussing your financial situation with a professional advisor, contact us today.

Brad Tatar

Join the Spotlight Asset Group Newsletter

The Pitfalls of Emotional Investing

People often make decisions based on emotion instead of rational deliberation. For example, that one friend you have who bought a new car they couldn’t afford because it but felt so incredibly nice to sit in it. I have a confession: that wasn’t a friend, it was me. The car was a black Ford Mustang. After finalizing the purchase and paying cash for the car, I remember reviewing my bank account and realizing I only had $11 to my name. Oh, and the car too. I was seventeen years old at the time and it was certainly not a sound investment decision on my part, it was an impulsive and emotional decision. I did have a lot of fun with that car if you’re wondering. But the truth is, if I put that hard-earned cash to better use by investing it and enjoying compound growth over several years, I would have been much better off. With the benefit of hindsight and years of experience and financial education, I now realize that the opportunity cost of that car was much more than the initial purchase price.

When it comes to investing, human behavior may cause us to make decisions based on emotion and not on fundamentals or rational deliberation. It’s a natural tendency. If you’ve been investing for some time you will certainly remember the tech bubble of 2000. Leading into that market, you could have invested in almost any tech start up and seen overnight success. But as we all know, that soon came to a screeching halt. The market is largely driven by supply and demand paired with fear and greed, as illustrated in the diagram below. Leading up to the tech bubble, investors saw double–digit returns and got greedy. This was followed by fear, or in this case, shear panic in 2002 following the Nasdaq drop of nearly 77% from top to bottom.

Consider some of the market corrections we saw in 2018 that were partly fueled by social media tweets about looming trade war concerns. Did large companies all announce poor earnings? No. Did the Fed make significant announcements or changes to rates at the time? No. Did job numbers or GDP reports come in much lower than expected? No. If nothing fundamentally changed, what caused the rise and fall of stock prices in those volatile times? Emotion.

Studies by Dalbar’s Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (see the chart by J.P. Morgan, below) have shown that, over the last twenty years, the average investor has experienced a return of just 2.1% while the S&P 500 returned 8.2%.

What accounts for this difference of more than 6% return on investment? A lot of it can be blamed on emotional decision-making, lack of discipline, and failure to diversify. Consider the lag effect and confidence when markets are high and peaking. This is generally a time that many investors are buying into the market, when in fact this is the ultimate time to sell and become more defensive or conservative. On the other hand, when markets are at the bottom it is a great opportunity to purchase stock or to take more aggressive positions. Think back to the 2008 financial crisis, when the S&P 500 lost 38% in a single year and every analyst featured on CNBC feared that the world was coming to an end. During that time, CNBC interviewed Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffet. I vividly remember the interview. Buffet, always the contrarian, compared the opportunity in the market to toilet paper being on sale at Walmart: he wouldn’t run away, he would be a buyer. A simple analogy from one of the smartest investors of our time.

During the crisis, many investors were pulling money out of the markets and moving it to cash to “wait on the sidelines.” After watching the Dow Jones Industrial Average drop from its peak of over 14,000 points in October 2007 to under 7,000 points by March 2009, and then climb back above 10,000 in less than nine months, I remember asking people when they were going to get back in. Most of them had no response, no plan. Many people never took the time to assess their re-entry point and timidly sat on the sidelines in cash, some never reinvesting back into their portfolios. Today’s market is almost double that of the pre-crisis peak. If these investors had stuck to their game plan, patiently waiting out only a few years of recovery following the worst crash since the Great Depression, they would have realized significant gains today and would have been even better off than they were before the crash.

Emotion can lead some investors to concentrate their portfolio in too few individual positions as well. I’ll never forget talking to a client, during the decline of General Motors, about the importance of diversification in his portfolio. This gentleman was a high school dropout who retired as a janitor, sweeping up the manufacturing facilities at one of the GM plants. He understood the importance of saving money and had fully invested his 401(k) in GM stock during a rising time for the company and auto industry. At the time of his retirement, he found himself not only fully invested in GM stock in his 401(k), but also his IRA, his wife’s retirement accounts, and their taxable nonretirement assets. This gentleman’s net worth was nearly $3,000,000 at the time of his retirement, not bad for a high school dropout. Despite conversations about his concentration risk and the importance of diversification and exit strategies, he stubbornly stayed invested in GM stock until all his combined accounts were worth less than $200,000 and GM neared bankruptcy. He was in denial for a long time, but he eventually realized that he let his emotions take control. The company he loved, and for which he worked so hard for nearly 50 years, was not the company he should have bet his entire retirement on. He was emotionally attached to GM because of his history with the company and the fond memories he had from his years of working there. He also was overconfident, as he had seen nothing but increases in GM’s production and the consistent growth of the auto industry, and he was comforted by the leadership he worked under during his tenure. This emotional attachment and overconfidence lead to one individual stock comprising his entire portfolio.

Technology has only exacerbated the problem with emotional investing and decision-making. Today, self-directed investors can get market information almost as quickly as a professional wealth manager, and quotes in real time. With this immediate flow of information, many investors make knee-jerk reactions to news because they fear monetary loss or missed opportunities. Part of what separates these self-directed investors from professional wealth managers is the ability to manage the emotional side of the markets through established processes and deliberative analysis. As professional wealth managers, our job is to take all the available data, sort through it, make sense of it, and act in accordance with pre-established goals and objectives, leaving emotion out of the equation.

As an advisor, it’s easy to discuss long-term trends with clients in the face of a poor year or a poor quarter. It is another thing to have that discussion during the boom years. If the markets have shown us anything over the years, it is that they themselves have no concept of emotion, fear, or greed. They just keep chugging along. Therefore, investors shouldn’t make decisions based on emotion, fear, or greed. This is easier said than done. It is difficult for some investors to grasp the concept of a strategy coming to fruition over several years, as opposed to the instant gratification of immediate investment success. I often find myself reminding my clients that their net worth was built over a lifetime and their investments should work equally as long and hard for them. The idea of the “get rich quick” scheme is simply not a realistic investment strategy. As advisors, we must act as educators and coaches of our clients, keeping them on track and helping them overcome the urge to make poor emotional investment decisions.

It’s no secret why most investors enjoy their best returns in their 401(k) plans. It’s not because they offer a better investment array or product offering. To the contrary, most 401(k) plans limit the investment options to a select group of mutual funds and limit the number of transactions allowed in a given time period. So why are their returns often so much better? It is because, within a 401(k) plan, employees are forced to diversify, stay disciplined, and dollar cost average into a defined investment plan that works over the life of their career.

The moral of the story? Stay disciplined while investing. Despite market movement and volatility, think logically and strategically about your investments. Good, sound financial planning is often the foundation to helping determine the right amount of risk and type of investment strategy you need to be confident, comfortable, and to stay the course.

Any time you have questions regarding your account, please reach out to your Spotlight Asset Group Wealth Manager. If you are not an existing client but are interested in discussing your financial situation with a professional advisor, contact us today.

Brad Tatar

Best Interest and Best Intentions

Best Interest and Best Intentions

An SEC vote aimed at helping retail investors could end up adding to their confusion.

Tomorrow, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) will vote on a package of rulemaking proposals aimed at protecting retail investors by, among other things, requiring brokers to act in the best interest of their customers. While the SEC’s intentions are good, I fear that the focus on labels (broker versus adviser) and on legal distinctions (“best interest” versus “fiduciary duty”) will only add to the confusion faced by many retail investors.

The world of wealth management can be a confusing, daunting place for the average investor. At the same time, there has never been more information available to the investing public. This apparent paradox is a problem that regulators and consumer advocacy groups have tried to address for years by, among other things, mandating more disclosures and imposing “plain English” requirements. Unfortunately, even the best intentions often have unintended consequences. Recent regulatory efforts seem to have added to the confusion by moving the concepts of “suitability” and “fiduciary duty” to the forefront, and those with a financial interest in the confusion (i.e. broker-dealers, investment advisers, and other financial professionals) have taken advantage.

Let’s take a step back and examine where all the confusion comes from. The financial services industry is populated by several types of financial professionals, including financial planners, insurance agents, accountants, estate planning attorneys, brokers, and investment advisers. Each of these professionals has different duties and legal obligations, including the fiduciary duty owed by investment advisers to their clients (which means they are held to the highest standard of conduct and must act in the best interest of their clients) and the duty of fair dealing owed by a broker to a customer (which, in part, means that they will only make recommendations to buy securities that are suitable for the customer).

These various players used to stick to their own turf and serve distinct needs of the investing public. For example, brokers typically buy and sell securities for their customers and, in return, the customers pay the broker commissions on the transactions. As long as a transaction is suitable for a customer (i.e. appropriate for the customer’s investment objectives), a broker can recommend a security that paid the broker a higher commission even if there were suitable alternatives that were cheaper for the customer (and therefore generated smaller commissions). On the other hand, investment advisers provide regular and continuous investment advice, usually to high net worth clients, for a fixed, asset-based fee. While there can be other fees involved, all fees have to be clearly disclosed to a client before the advisory relationship begins.

These days, any given financial professional or entity might offer two or more products or services (insurance, financial planning, estate planning, stock trading, and investment management), this includes companies that are registered as both investment advisers and broker-dealers. These so-called “hybrids” act as investment advisers in some situations and as brokers in others. Needless to say, the duties, legal obligations, and compensation structure of such companies can be murky at best.

The SEC introduced its current proposals way back in April of 2018 in an attempt to clear up the confusion. These proposals are intended to “enhance the quality and transparency of investors’ relationships with investment advisers and broker-dealers while preserving access to a variety of types of advice relationships and investment products.”[1] Easier said than done.

The most ambitious of these proposals, known as Regulation Best Interest, has garnered the most attention. It would require broker-dealers to “act in the best interest of a retail customer when making a recommendation of any securities transaction or investment strategy involving securities to a retail customer [and] … make it clear that a broker-dealer may not put its financial interests ahead of the interests of a retail customer in making recommendations.” Another proposal is “an interpretation to reaffirm and, in some cases, clarify the [SEC’s] views of the fiduciary duty that investment advisers owe to their clients,” which, as the SEC says, includes the obligation to “act in the best interest of its client.”[2] The SEC believes that “[by] highlighting principles relevant to the fiduciary duty, investment advisers and their clients would have greater clarity about advisers’ legal obligations.”

As an aside, it seems reasonable to assume that any investment professional will act in the best interest of their clients or customers. However just because they are supposed to act a certain way doesn’t mean that they will. The SEC’s website is full of enforcement actions against investment advisers that failed to uphold their fiduciary duties.

These two proposals have yet to be implemented by the SEC, but they have already sparked a fierce debate among brokers and advisers, some of whom believe that all financial professionals should be held to the fiduciary standard and others who think there was nothing wrong with the status quo. The proposals also appear to have spurred a new wave of marketing, with some firms touting the fact that they are fiduciaries and that they don’t accept commissions and others talking more about their low brokerage fees.

The additional disclosure and marketing prompted by the SEC’s proposals is great, but I fear that in all the noise of the suitability/broker vs. fiduciary/adviser argument that the real jewel of the SEC’s proposals is being missed. People who are looking to hire a financial professional shouldn’t do so based on a label, the label is only one part of the equation. Investors needs to take a deeper look under the hood to find out exactly what they are getting.

The SEC’s third proposal aims to allow investors to do just that by requiring brokers and advisers to provide their clients with a new short-form disclosure document, referred to as Form CRS (short for client relationship summary), that would “provide retail investors with simple, easy-to-understand information about the nature of their relationship with their investment professional” and supplement other, more detailed disclosures. For advisers, those detailed disclosures would be those found in Form ADV, which advisers are already required to provide to their clients. For brokers, the detailed disclosures would be those required under Regulation Best Interest (which, again, has not been enacted).

I believe that Form CRS would make a real difference in the industry by laying out the key distinctions between an independent investment adviser (i.e. an investment adviser that is not also a dually registered has no broker-dealer affiliation) and a broker-dealer. Moreover, for clients of an investment adviser, the ADV is typically the primary source of the adviser’s disclosures. But the ADV can run dozens of pages long and is often drafted by a law firm hired by the adviser. They often contain so much legalese and such detailed disclosure language that it can be very difficult for most people to read and understand, if they even bother to read it at all. As a result, it is easy to miss a lot of the important disclosures relating to fees, conflicts of interests, and regulatory events. Form CRS can be a better vehicle for disclosing these key issues in a simple, straight-forward way. Form CRS is supposed to be no more than four pages long and would disclose the services offered, fees and costs, conflicts of interest, and any regulatory disclosures such as disciplinary events and complaints.

At Spotlight Asset Group, we felt so strongly that Form CRS is the direction the industry needs to go that we came up with our own document ahead of the SEC finalizing any of these rules. Our “Prospect Proposal” is a two-page document that highlights all of the information we feel is important for prospects to know before they sign up with us as a client. This includes the services we will provide, the fees they will be charged as both a percentage and as a dollar amount, any additional costs like trading commissions or expense ratios, any material conflicts of interest we may have, and how their individual investment adviser representative is compensated. If at some point we have a regulatory or disciplinary item that should be disclosed, we would disclose it in our Prospect Proposal. We are working to implement the use of the Prospect Proposal across the firm because we believe that it is important to be completely transparent with our clients at the outset of the relationship. Not only is this fair, it serves to set the tone for an open dialogue and cooperative partnership with our clients. As noted in a recent Intelligent Investor editorial by Jason Zweig of the Wall Street Journal, this dialogue is the real key to a good relationship between a financial advisor and their client.[3]

I think such upfront disclosures are vitally important and should become the standard for all financial professionals. While the current disclosure documents lay out an adviser’s duties or a broker’s obligations, in my 15 years in the investment business I can count on one hand the number of clients who have asked questions about disclosures in an ADV or other document. It doesn’t happen often because a lot of people don’t read them. Wouldn’t it be better if a financial professional had to proactively go through all relevant information with a prospective client or customer before they signed on the dotted line? That is the argument we should be focusing on, not a confusing discussion about who is a fiduciary and what that means.

[1] See SEC Proposes to Enhance Protections and Preserve Choice for Retail Investors in Their Relationships With Investment Professionals at https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2018-68 (April 18, 2018) (emphasis added).

[2] See Regulation Best Interest, Release No, 34-83062, available at https://www.sec.gov/rules/proposed/2018/34-83062.pdf (April 18, 2018) (emphasis added).

[3] Jason Zweig, A New Rule Won’ Make Your Broker an Angel, available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-new-rule-wont-make-your-broker-an-angel-11559313036?mod=hp_lead_pos11 (May 31, 2019).

Stephen Greco, CEO

Join the Spotlight Asset Group Newsletter

Best Interest and Best Intentions

An SEC vote aimed at helping retail investors could end up adding to their confusion.

Tomorrow, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) will vote on a package of rulemaking proposals aimed at protecting retail investors by, among other things, requiring brokers to act in the best interest of their customers. While the SEC’s intentions are good, I fear that the focus on labels (broker versus adviser) and on legal distinctions (“best interest” versus “fiduciary duty”) will only add to the confusion faced by many retail investors.

The world of wealth management can be a confusing, daunting place for the average investor. At the same time, there has never been more information available to the investing public. This apparent paradox is a problem that regulators and consumer advocacy groups have tried to address for years by, among other things, mandating more disclosures and imposing “plain English” requirements. Unfortunately, even the best intentions often have unintended consequences. Recent regulatory efforts seem to have added to the confusion by moving the concepts of “suitability” and “fiduciary duty” to the forefront, and those with a financial interest in the confusion (i.e. broker-dealers, investment advisers, and other financial professionals) have taken advantage.

Let’s take a step back and examine where all the confusion comes from. The financial services industry is populated by several types of financial professionals, including financial planners, insurance agents, accountants, estate planning attorneys, brokers, and investment advisers. Each of these professionals has different duties and legal obligations, including the fiduciary duty owed by investment advisers to their clients (which means they are held to the highest standard of conduct and must act in the best interest of their clients) and the duty of fair dealing owed by a broker to a customer (which, in part, means that they will only make recommendations to buy securities that are suitable for the customer).

These various players used to stick to their own turf and serve distinct needs of the investing public. For example, brokers typically buy and sell securities for their customers and, in return, the customers pay the broker commissions on the transactions. As long as a transaction is suitable for a customer (i.e. appropriate for the customer’s investment objectives), a broker can recommend a security that paid the broker a higher commission even if there were suitable alternatives that were cheaper for the customer (and therefore generated smaller commissions). On the other hand, investment advisers provide regular and continuous investment advice, usually to high net worth clients, for a fixed, asset-based fee. While there can be other fees involved, all fees have to be clearly disclosed to a client before the advisory relationship begins.

These days, any given financial professional or entity might offer two or more products or services (insurance, financial planning, estate planning, stock trading, and investment management), this includes companies that are registered as both investment advisers and broker-dealers. These so-called “hybrids” act as investment advisers in some situations and as brokers in others. Needless to say, the duties, legal obligations, and compensation structure of such companies can be murky at best.

The SEC introduced its current proposals way back in April of 2018 in an attempt to clear up the confusion. These proposals are intended to “enhance the quality and transparency of investors’ relationships with investment advisers and broker-dealers while preserving access to a variety of types of advice relationships and investment products.”[1] Easier said than done.

The most ambitious of these proposals, known as Regulation Best Interest, has garnered the most attention. It would require broker-dealers to “act in the best interest of a retail customer when making a recommendation of any securities transaction or investment strategy involving securities to a retail customer [and] … make it clear that a broker-dealer may not put its financial interests ahead of the interests of a retail customer in making recommendations.” Another proposal is “an interpretation to reaffirm and, in some cases, clarify the [SEC’s] views of the fiduciary duty that investment advisers owe to their clients,” which, as the SEC says, includes the obligation to “act in the best interest of its client.”[2] The SEC believes that “[by] highlighting principles relevant to the fiduciary duty, investment advisers and their clients would have greater clarity about advisers’ legal obligations.”

As an aside, it seems reasonable to assume that any investment professional will act in the best interest of their clients or customers. However just because they are supposed to act a certain way doesn’t mean that they will. The SEC’s website is full of enforcement actions against investment advisers that failed to uphold their fiduciary duties.

These two proposals have yet to be implemented by the SEC, but they have already sparked a fierce debate among brokers and advisers, some of whom believe that all financial professionals should be held to the fiduciary standard and others who think there was nothing wrong with the status quo. The proposals also appear to have spurred a new wave of marketing, with some firms touting the fact that they are fiduciaries and that they don’t accept commissions and others talking more about their low brokerage fees.

The additional disclosure and marketing prompted by the SEC’s proposals is great, but I fear that in all the noise of the suitability/broker vs. fiduciary/adviser argument that the real jewel of the SEC’s proposals is being missed. People who are looking to hire a financial professional shouldn’t do so based on a label, the label is only one part of the equation. Investors needs to take a deeper look under the hood to find out exactly what they are getting.

The SEC’s third proposal aims to allow investors to do just that by requiring brokers and advisers to provide their clients with a new short-form disclosure document, referred to as Form CRS (short for client relationship summary), that would “provide retail investors with simple, easy-to-understand information about the nature of their relationship with their investment professional” and supplement other, more detailed disclosures. For advisers, those detailed disclosures would be those found in Form ADV, which advisers are already required to provide to their clients. For brokers, the detailed disclosures would be those required under Regulation Best Interest (which, again, has not been enacted).

I believe that Form CRS would make a real difference in the industry by laying out the key distinctions between an independent investment adviser (i.e. an investment adviser that is not also a dually registered has no broker-dealer affiliation) and a broker-dealer. Moreover, for clients of an investment adviser, the ADV is typically the primary source of the adviser’s disclosures. But the ADV can run dozens of pages long and is often drafted by a law firm hired by the adviser. They often contain so much legalese and such detailed disclosure language that it can be very difficult for most people to read and understand, if they even bother to read it at all. As a result, it is easy to miss a lot of the important disclosures relating to fees, conflicts of interests, and regulatory events. Form CRS can be a better vehicle for disclosing these key issues in a simple, straight-forward way. Form CRS is supposed to be no more than four pages long and would disclose the services offered, fees and costs, conflicts of interest, and any regulatory disclosures such as disciplinary events and complaints.

At Spotlight Asset Group, we felt so strongly that Form CRS is the direction the industry needs to go that we came up with our own document ahead of the SEC finalizing any of these rules. Our “Prospect Proposal” is a two-page document that highlights all of the information we feel is important for prospects to know before they sign up with us as a client. This includes the services we will provide, the fees they will be charged as both a percentage and as a dollar amount, any additional costs like trading commissions or expense ratios, any material conflicts of interest we may have, and how their individual investment adviser representative is compensated. If at some point we have a regulatory or disciplinary item that should be disclosed, we would disclose it in our Prospect Proposal. We are working to implement the use of the Prospect Proposal across the firm because we believe that it is important to be completely transparent with our clients at the outset of the relationship. Not only is this fair, it serves to set the tone for an open dialogue and cooperative partnership with our clients. As noted in a recent Intelligent Investor editorial by Jason Zweig of the Wall Street Journal, this dialogue is the real key to a good relationship between a financial advisor and their client.[3]

I think such upfront disclosures are vitally important and should become the standard for all financial professionals. While the current disclosure documents lay out an adviser’s duties or a broker’s obligations, in my 15 years in the investment business I can count on one hand the number of clients who have asked questions about disclosures in an ADV or other document. It doesn’t happen often because a lot of people don’t read them. Wouldn’t it be better if a financial professional had to proactively go through all relevant information with a prospective client or customer before they signed on the dotted line? That is the argument we should be focusing on, not a confusing discussion about who is a fiduciary and what that means.

[1] See SEC Proposes to Enhance Protections and Preserve Choice for Retail Investors in Their Relationships With Investment Professionals at https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2018-68 (April 18, 2018) (emphasis added).

[2] See Regulation Best Interest, Release No, 34-83062, available at https://www.sec.gov/rules/proposed/2018/34-83062.pdf (April 18, 2018) (emphasis added).

[3] Jason Zweig, A New Rule Won’ Make Your Broker an Angel, available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-new-rule-wont-make-your-broker-an-angel-11559313036?mod=hp_lead_pos11 (May 31, 2019).

Stephen Greco, CEO

Where Does Your Advisor Get Their Clients?

Where Does Your Advisor Get Their Clients?

Understanding how an RIA gets clients can be an important factor for prospective clients or for advisors looking to join an RIA.

Every registered investment adviser (RIA) is looking for the same thing, more clients. Understanding how an RIA gets their clients can be an important consideration for prospective clients of an RIA and for individual financial advisors looking to join an RIA.

RIAs use various tools to develop clients and grow their business. The particular business development model used by an RIA can give you valuable insight into, among other things, how the company may work with you and what is important to them. So, let’s take a look at the different models and how they can affect you as an end user …

Organic Referrals

One of the most common ways RIAs get new clients is through what I will refer to as “organic” referrals from existing clients. An organic referral typically involves an existing client of an RIA who provides the RIA with a potential client introduction without receiving anything of value in return. Most RIAs use organic referrals as at least one component of their business development plan, and indeed for some it is their only avenue for growth. What does that tell a prospective client or an advisor looking to join the RIA? Usually, if an RIA is receiving a lot of organic referrals from existing clients, it is reasonable to assume that they are doing a good job for their clients. Otherwise, clients wouldn’t be referring friends, family members, and colleagues and risking those relationships. So, it is worthwhile to ask an RIA about the percentage of their client growth that comes through organic referrals from existing clients.

Similar to an organic referral from an existing client, an RIA might also receive referrals from a professional service provider, such as an estate planning attorney or certified public accountant, with whom the RIA has an existing relationship. In some such cases, the attorney or CPA simply does so to develop a relationship with the RIA with the hope that the flow of referrals will go both ways.

Paid Referrals/Solicitations

On the other side of the spectrum, an RIA might obtain new clients through paid leads. For example, an RIA also might get new clients from affiliated broker-dealers who serve as custodians for the RIA or perform other services. Most of the discount brokerage companies (e.g. Fidelity, Schwab, TD Ameritrade) have referral programs where they send certain clients to pre-screened RIAs for wealth management services. In return, those brokerage companies may receive a portion of the fee paid by the client to the RIA, typically 0.25%. In some situations, this referral fee might continue for as long as the client stays with the RIA. While there may be several other factors that lead a broker to refer a client to a certain RIA, the possibility of a referral fee is certainly one that should be considered when a client is deciding whether to hire a particular RIA. Therefore, it is important to ask the broker who makes the referral if they have sales targets they need to meet and/or if they personally benefit from the referral. Don’t just assume they are doing it out of the kindness of their heart. Another example is a situation similar to that which I described earlier where an attorney or CPA refers his or her own clients to an RIA, but the RIA pays the attorney or CPA either a flat fee or a percentage of the fees billed to the client.

RIAs can also use third-party solicitors to find new clients. In this scenario, the RIA pays a cash fee to someone who is not an employee of the RIA to find clients and make introductions. Oftentimes this fee is a portion of the advisory fee charged to the client for a certain period of time. There is nothing inherently wrong with such arrangements, or other referral situations in which an RIA pays for client leads. However, such arrangements should be disclosed to the client so that they can evaluate the potential conflict of interest and make an informed decision. Such referral arrangements should be disclosed in two ways. First, the person making the referral (and being paid for it) should provide the prospective client with a document that discloses certain information about his or her arrangement with the RIA, including the fee to be paid. Second, the RIA should disclose such arrangements in the Form ADV that they file with the SEC, which can usually be found at www.adviserinfo.sec.gov.

A paid solicitation is different from an unpaid referral, and a prospective client might have a very different perception of client growth based on referrals from people who expect nothing in return versus growth based on paid solicitations. This is just one more piece of information that a prospective client should have in hand when deciding whether to hire an RIA.

Mergers & Acquisitions

Lastly, advisors can grow through acquiring, or merging with, existing advisory firms. There are several firms out there that will buy out an existing firm entirely. Such a model can be efficient and effective because, as you create economies of scale and grow larger and larger, it gets easier to bring on more RIAs to take advantage of that scale. There also are a handful of companies out there that have become the predominant players in what is considered the “roll-up” market for advisors. There are a number of reasons that a prospective client should know if the RIA they are considering is one of these companies. For example, the rate of an RIA’s growth might impact their ability to provide services to their clients at the same level if the RIA is not built to handle that scale.

So why is all of this important? The bottom line is that, for many people looking for someone to help them with their financial planning and investments, size matters. At the same time, a lot of the marketing and promotional aspects of the investment advisory business focus on size, specifically the amount of assets under management, or AUM, of an RIA. For example, rate of growth is one of the primary ways that advisors are ranked by various publications. Therefore, while size can be important for many reasons, it is important to look deeper into the metrics one uses to evaluate an RIA’s size.

It is important to understand where an RIA’s growth is coming from in order to evaluate if they are truly living up to the expectations of their clients. One of the most impressive growth indicators for a company is if they are receiving a substantial number of referrals from existing clients. However, that growth might be viewed differently if they are growing because of paid solicitation programs. Similarly, if they are expanding because they are acquiring other advisors, it could lend a different interpretation of rapid growth in AUM.

None of these models are necessarily good or bad for prospective clients, but it is something to keep in mind. It is also important that your RIA is upfront with you about these and other issues. At my firm, Spotlight Asset Group, we have found clients through both referrals from existing clients and by bringing on existing advisory firms or individual advisors. While we don’t currently participate in any paid solicitation programs, it is something that we would consider under the right circumstances. No matter what approach we take, we always ask ourselves how it best serves both our existing clients and prospective clients.

Stephen Greco, CEO

Join the Spotlight Asset Group Newsletter

Where Does Your Advisor Get Their Clients?

Understanding how an RIA gets clients can be an important factor for prospective clients or for advisors looking to join an RIA.

Every registered investment adviser (RIA) is looking for the same thing, more clients. Understanding how an RIA gets their clients can be an important consideration for prospective clients of an RIA and for individual financial advisors looking to join an RIA.

RIAs use various tools to develop clients and grow their business. The particular business development model used by an RIA can give you valuable insight into, among other things, how the company may work with you and what is important to them. So, let’s take a look at the different models and how they can affect you as an end user …

Organic Referrals

One of the most common ways RIAs get new clients is through what I will refer to as “organic” referrals from existing clients. An organic referral typically involves an existing client of an RIA who provides the RIA with a potential client introduction without receiving anything of value in return. Most RIAs use organic referrals as at least one component of their business development plan, and indeed for some it is their only avenue for growth. What does that tell a prospective client or an advisor looking to join the RIA? Usually, if an RIA is receiving a lot of organic referrals from existing clients, it is reasonable to assume that they are doing a good job for their clients. Otherwise, clients wouldn’t be referring friends, family members, and colleagues and risking those relationships. So, it is worthwhile to ask an RIA about the percentage of their client growth that comes through organic referrals from existing clients.

Similar to an organic referral from an existing client, an RIA might also receive referrals from a professional service provider, such as an estate planning attorney or certified public accountant, with whom the RIA has an existing relationship. In some such cases, the attorney or CPA simply does so to develop a relationship with the RIA with the hope that the flow of referrals will go both ways.

Paid Referrals/Solicitations

On the other side of the spectrum, an RIA might obtain new clients through paid leads. For example, an RIA also might get new clients from affiliated broker-dealers who serve as custodians for the RIA or perform other services. Most of the discount brokerage companies (e.g. Fidelity, Schwab, TD Ameritrade) have referral programs where they send certain clients to pre-screened RIAs for wealth management services. In return, those brokerage companies may receive a portion of the fee paid by the client to the RIA, typically 0.25%. In some situations, this referral fee might continue for as long as the client stays with the RIA. While there may be several other factors that lead a broker to refer a client to a certain RIA, the possibility of a referral fee is certainly one that should be considered when a client is deciding whether to hire a particular RIA. Therefore, it is important to ask the broker who makes the referral if they have sales targets they need to meet and/or if they personally benefit from the referral. Don’t just assume they are doing it out of the kindness of their heart. Another example is a situation similar to that which I described earlier where an attorney or CPA refers his or her own clients to an RIA, but the RIA pays the attorney or CPA either a flat fee or a percentage of the fees billed to the client.

RIAs can also use third-party solicitors to find new clients. In this scenario, the RIA pays a cash fee to someone who is not an employee of the RIA to find clients and make introductions. Oftentimes this fee is a portion of the advisory fee charged to the client for a certain period of time. There is nothing inherently wrong with such arrangements, or other referral situations in which an RIA pays for client leads. However, such arrangements should be disclosed to the client so that they can evaluate the potential conflict of interest and make an informed decision. Such referral arrangements should be disclosed in two ways. First, the person making the referral (and being paid for it) should provide the prospective client with a document that discloses certain information about his or her arrangement with the RIA, including the fee to be paid. Second, the RIA should disclose such arrangements in the Form ADV that they file with the SEC, which can usually be found at www.adviserinfo.sec.gov.

A paid solicitation is different from an unpaid referral, and a prospective client might have a very different perception of client growth based on referrals from people who expect nothing in return versus growth based on paid solicitations. This is just one more piece of information that a prospective client should have in hand when deciding whether to hire an RIA.

Mergers & Acquisitions

Lastly, advisors can grow through acquiring, or merging with, existing advisory firms. There are several firms out there that will buy out an existing firm entirely. Such a model can be efficient and effective because, as you create economies of scale and grow larger and larger, it gets easier to bring on more RIAs to take advantage of that scale. There also are a handful of companies out there that have become the predominant players in what is considered the “roll-up” market for advisors. There are a number of reasons that a prospective client should know if the RIA they are considering is one of these companies. For example, the rate of an RIA’s growth might impact their ability to provide services to their clients at the same level if the RIA is not built to handle that scale.

So why is all of this important? The bottom line is that, for many people looking for someone to help them with their financial planning and investments, size matters. At the same time, a lot of the marketing and promotional aspects of the investment advisory business focus on size, specifically the amount of assets under management, or AUM, of an RIA. For example, rate of growth is one of the primary ways that advisors are ranked by various publications. Therefore, while size can be important for many reasons, it is important to look deeper into the metrics one uses to evaluate an RIA’s size.

It is important to understand where an RIA’s growth is coming from in order to evaluate if they are truly living up to the expectations of their clients. One of the most impressive growth indicators for a company is if they are receiving a substantial number of referrals from existing clients. However, that growth might be viewed differently if they are growing because of paid solicitation programs. Similarly, if they are expanding because they are acquiring other advisors, it could lend a different interpretation of rapid growth in AUM.

None of these models are necessarily good or bad for prospective clients, but it is something to keep in mind. It is also important that your RIA is upfront with you about these and other issues. At my firm, Spotlight Asset Group, we have found clients through both referrals from existing clients and by bringing on existing advisory firms or individual advisors. While we don’t currently participate in any paid solicitation programs, it is something that we would consider under the right circumstances. No matter what approach we take, we always ask ourselves how it best serves both our existing clients and prospective clients.

Stephen Greco, CEO